Columbia Records

| Columbia Records | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Parent company | Sony Music Entertainment |

| Founded | 1888 (until 1894 as a subsidiary of the North American Phonograph Company) |

| Distributor(s) | Columbia/Epic Label Group (In the US) |

| Genre | Various |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Official Website | columbiarecords.com |

Columbia Records is an American record label, owned by Sony Music Entertainment, and operates as an imprint of the Columbia/Epic Label Group. It was founded in 1888, evolving from an earlier enterprise, the American Graphophone Company — successor to the Volta Graphophone Company.[1] Columbia is the oldest surviving brand name in pre-recorded sound,[2] being the first record company to produce pre-recorded records as opposed to blank cylinders. Columbia Records went on to release records by an array of notable singers, instrumentalists and groups. From 1961 to 1990, its recordings were released outside the U.S. and Canada on the CBS Records label before adopting the Columbia name in most of the world.

Until 1989, Columbia Records had no connection to Columbia Pictures, which used various other names for record labels they owned, including Colpix, and later Arista; rather it was connected to CBS (which stood for Columbia Broadcasting System), the former owner. That label is now a sister label to Columbia Records through Sony Music; both are connected to Columbia Pictures through Sony Corporation of America, worldwide parent of both the music and motion picture arms of Sony.

Contents |

History

Beginnings

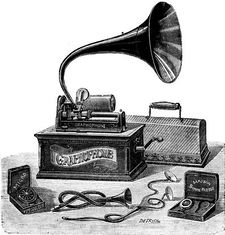

The Columbia Phonograph Company was originally the local company run by Edward Easton, distributing and selling Edison phonographs and phonograph cylinders in Washington, D.C., Maryland and Delaware, and derives its name from the District of Columbia, which was its headquarters. As was the custom of some of the regional phonograph companies, Columbia produced many commercial cylinder recordings of its own, and its catalogue of musical records in 1891 was 10 pages long. Columbia's ties to Edison and the North American Phonograph Company were severed in 1894 with the North American Phonograph Company's breakup, and thereafter sold only records and phonographs of its own manufacture. In 1902, Columbia introduced the "XP" record, a molded brown wax record, to use up old stock. Columbia introduced "black wax" records in 1903, and, according to Tim Gracyk, continued to mold brown waxes until 1904; the highest number known to Gracyk is 32601, Heinie, which is a duet by Arthur Collins and Byron G. Harlan. According to Gracyk, the molded brown waxes may have been sold to Sears for distribution (possibly under Sears' "Oxford" trademark for Columbia products).[3]

Columbia began selling disc records and phonographs in addition to the cylinder system in 1901, preceded only by their "Toy Graphophone" of 1899, which used small, vertically-cut records. For a decade, Columbia competed with both the Edison Phonograph Company cylinders and the Victor Talking Machine Company disc records as one of the top three names in American recorded sound.

In order to add prestige to its early catalogue of artists, Columbia contracted a number of New York Metropolitan Opera stars to make recordings (from 1903 onwards). These stars included Marcella Sembrich, Lillian Nordica, Antonio Scotti and Edouard de Reszke, but the technical standard of their recordings were not considered to be as high as the results achieved with classical singers during the pre-World War One period by Victor, Edison, England's His Master's Voice or Italy's Fonotipia Records. In 1908, Columbia commenced the mass production of "Double Sided" discs, with the recording grooves stamped into both faces of each disc — not just one. The firm also introduced the internal-horn "Grafonola" to compete with the extremely popular "Victrola" sold by the rival Victor Talking Machine Company.

During this era, Columbia used the famous "Magic Notes" logo — a pair of sixteenth notes (semiquavers) in a circle — both in the United States and overseas (where this particular logo would never substantially change).

Columbia stopped recording and manufacturing wax cylinder records in 1908, after arranging to issue celluloid cylinder records made by the Indestructible Record Company of Albany, New York, as "Columbia Indestructible Records." In July 1912, Columbia decided to concentrate exclusively on disc records and stopped manufacturing cylinder phonographs although they continued selling Indestructible's cylinders under the Columbia name for a year or two more.

In late 1923, Columbia went into receivership. The company was bought by their English subsidiary, the Columbia Graphophone Company in 1925 and the label, record numbering system, and recording process changed (the "New Process" [still acoustic] was used on budget labels until 1930). See more at American Columbia single record cataloging systems. On February 25, 1925, Columbia began recording with the new electric recording process licensed from Western Electric. The new "Viva-tonal" records set a benchmark in tone and clarity unequalled on commercial discs during the "78-rpm" era. The first electrical recordings were made by Art Gillham, the popular "Whispering Pianist." In a secret agreement with Victor, both companies did not make the new recording technology public knowledge for some months, in order not to hurt sales of their existing acoustically recorded catalogue while a new electrically recorded catalogue was being built.

In 1926, Columbia acquired Okeh Records and its growing stable of jazz and blues artists including Louis Armstrong and Clarence Williams. (Columbia has already built an impressive catalog of blues and jazz artists including Bessie Smith). In 1928, Paul Whiteman, the nation's most popular orchestra leader, left Victor to record for Columbia. That same year, Columbia executive Frank Buckley Walker pioneered some of the first country music or "hillbilly" genre recordings in Johnson City, Tennessee including artists such as Clarence Horton Greene and the legendary fiddler and entertainer, "Fiddlin'" Charlie Bowman. 1929 saw industry legend Ben Selvin signing on as house bandleader and A. & R. director. Other favorites in the Viva-tonal era included Ruth Etting, Fletcher Henderson and Ted Lewis. Columbia kept using acoustic recording for "budget label" pop product well into 1929 on the Harmony, Velvet Tone (both general purpose labels) and Diva (sold exclusively at W.T. Grant stores). 1929 was also the year that Columbia's older rival and former affiliate Edison Records folded to make Columbia the oldest surviving record label.

Columbia ownership separation

In 1931, the British Columbia Graphophone Company (itself originally a subsidiary of American Columbia Records, then to become independent, actually went on to purchase its former parent, American Columbia, in late 1929) merged with the Gramophone Company to form Electric & Musical Industries Ltd. (EMI). EMI was forced to sell its American Columbia operations (because of anti-trust concerns) to the Grigsby-Grunow Company, makers of the Majestic Radio. But Majestic soon fell on hard times. An abortive attempt in 1932 (around the same time that Victor was experimenting with their 33 1/3 "program transcriptions") was the "Longer Playing Record", a finer-grooved 10" 78 with 4:30 to 5:00 playing time per side. Columbia issued about 8 of these (in the 18000-D series), as well as a short-lived series of double-grooved "Longer Playing Record"s on its Harmony, Clarion and Velvet Tone labels. All of these experiments (and indeed the Harmony, Velvet Tone and Clarion labels) were discontinued by mid-1932.

A longer-lived marketing ploy was the Columbia "Royal Blue Record," a brilliant blue laminated product with matching label. Royal Blue issues, made from late 1932 through 1935, are particularly popular with collectors for their rarity and musical interest. The C.P. MacGregor Company, an independent recording studio in Oakland, California, did Columbia's pressings for sale west of the Rockies and continued using the Royal Blue material for these until about mid-1936. It was also used for their own radio-only music library.

But with the Great Depression's tightened economic stranglehold on the country, in a day when the phonograph itself had become a passé luxury, nothing slowed Columbia's decline. Yet, despite this, it was still producing some of the most remarkable records of the day, especially on sessions produced by John Hammond and financed by EMI for overseas release. Grigsby-Grunow went under in 1934, and was forced to sell Columbia for a mere $70,000 to the American Record Corporation (ARC).[4] This combine already included Brunswick as its premium label, so Columbia was relegated to slower sellers such as the Hawaiian music of Andy Iona, the Irving Mills stable of artists and songs, and the still unknown Benny Goodman. By late 1936, pop releases were discontinued, leaving the label essentially defunct.

Then, in 1935, Herbert M. Greenspon, an 18-year-old shipping clerk, led a committee to organize the first trade union shop at the main manufacturing factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Elected as president of the Congress of Industrial Unions (CIO) local, Greenspon negotiated the first contract between factory workers and Columbia management. In a career with Columbia that lasted 30 years, Greenspon retired after achieving the position of executive vice president of the company.

As southern gospel developed, Columbia had astutely sought to record the artists associated with that aspiring genre, being, for example, the first and only company to record Charles Davis Tillman. But most fortuitously for Columbia in its Depression Era financial woes, in 1936 the company entered into an exclusive recording contract with the Chuck Wagon Gang, in a symbiotic relationship which continued into the 1970s. The Chuck Wagon Gang, a signature group of southern gospel, became Columbia's bestsellers, with at least 37 million records,[5] many of them through the aegis of the Mull Singing Convention of the Air sponsored on radio (and later television) by southern gospel broadcaster J. Bazzel Mull (1914–2006).

CBS takes over

In 1938 ARC, including the Columbia label in the USA, was bought by William S. Paley of the Columbia Broadcasting System for US$750,000.[6] (Columbia Records had originally co-founded CBS in 1927 along with New York talent agent Arthur Judson, but soon cashed out of the partnership leaving only the name; Paley acquired the fledgling radio network in 1928.) CBS revived the Columbia label in the place of Brunswick and the Okeh label in the place of Vocalion. CBS retained control of all of ARC's past masters, but in a complicated move, the pre-1931 Brunswick and Vocalion masters, as well as trademarks of Brunswick and Vocalion reverted back to Warner Brothers (who had leased their whole recording operation to ARC in early 1932) and Warners sold the lot to Decca Records in 1941.[7]

The Columbia trademark from this point until the late 1950s was two overlapping circles with the Magic Notes in the left circle and a CBS microphone in the right circle. The Royal Blue labels now disappeared in favor of a deep red, which caused RCA Victor to claim infringement on its "Red Seal" trademark. (RCA lost the case.) The blue Columbia label was kept for its classical music Columbia Masterworks Records line until it was later changed to a green label before switching to a gray label in the late 1950s, and then to the bronze that is familiar to owners of its classical and Broadway albums. Columbia Phonograph Company of Canada did not survive the Great Depression, so CBS made a distribution deal with Sparton Records in 1939 to release Columbia records in Canada under the Columbia name.

In 1947, CBS founded its Mexican record company, Discos Columbia de Mexico.[8]

The LP record

Columbia's president Ted Wallerstein, instrumental in steering Paley to the ARC purchase, at this time set his talents to the goal (as he saw it) of hearing an entire movement of a symphony on one side of an album. Ward Botsford writing for the Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Issue of "High Fidelity Magazine" relates, "He was no inventor—he was simply a man who seized an idea whose time was ripe and begged, ordered, and cajoled a thousand men into bringing into being the now accepted medium of the record business." Despite Wallerstein's stormy tenure, in 1948 Columbia introduced the Long Playing microgroove (LP) record (sometimes in early advertisements Lp) format, which rotated at 33⅓ revolutions per minute, to be the standard for the gramophone record for half a century. CBS research director Dr. Peter Goldmark played a managerial role in the collaborative effort, but Wallerstein credits engineer William Savory with the technical prowess that brought the long-playing disc to the public. By the early 1940s, Columbia had been experimenting with higher fidelity recordings, as well as longer masters, which paved the way for the successful release of the LPs in 1948. One such record that helped set a new standard for music listeners was the 10" LP reissue of The Voice of Frank Sinatra, originally released on March 4, 1946 as an album of four 78 rpm records, which was the first pop album issued in the new LP format. Sinatra was arguably Columbia's hottest commodity and his artistic vision combined with the direction Columbia were taking the medium of music, both popular and classic, were well suited. The Voice of Frank Sinatra was also considered to be the first genuine concept album.

Columbia's LPs were particularly well-suited to classical music's longer pieces, so some of the early albums featured such artists as Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra, Bruno Walter and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, and Sir Thomas Beecham and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. The success of these recordings eventually persuaded Capitol Records to begin releasing LPs in 1949. RCA Victor began releasing LPs in 1950, quickly followed by other major American labels. (Decca Records in the U.K. was the first to release LPs in Europe, beginning in 1949.)

An "original cast recording" of Rodgers & Hammerstein's South Pacific with Ezio Pinza and Mary Martin was recorded in 1949. Both conventional metal masters and tape were used in the sessions in New York City. For some reason, the taped version was not used until Sony released it as part of a set of CDs devoted to Columbia's Broadway albums.[9] Over the years, Columbia joined Decca and RCA Victor in specializing in albums devoted to Broadway musicals with members of the original casts. In the 1950s, Columbia also began releasing LPs drawn from the soundtracks of popular films.

The 1950s

In 1951, Columbia USA began issuing records in the 45 rpm format RCA had introduced two years earlier.[10] Also that year, Columbia USA severed its decades-long distribution arrangement with EMI and signed a distribution deal with Philips Records to market Columbia recordings outside North America. EMI continued to distribute Okeh, and later Epic, label recordings for several years into the 1960s. EMI also continued to distribute Columbia recordings in Australia and New Zealand.

Columbia became the most successful non-rock record company in the 1950s when they lured impresario Mitch Miller away from the Mercury label (Columbia remained largely uninterested in the teenage rock market until the early 1960s, despite a handful of crossover hits). Miller quickly signed on Mercury's biggest artist at the time, Frankie Laine, and discovered several of the decade's biggest recording stars including Tony Bennett, Jimmy Boyd, Guy Mitchell, Johnnie Ray, The Four Lads, Rosemary Clooney, Ray Conniff and Johnny Mathis. He also oversaw many of the early singles of the label's top female recording star of the decade, Doris Day. In 1953, CBS formed Columbia's sister label Epic Records. 1954 saw Columbia end its distribution arrangement with Sparton Records and form Columbia Records of Canada.[11]

With 1955, Columbia USA decisively broke with its past when it introduced its new, modernist-style "Walking Eye" logo, designed by Columbia's art director Neil Fujita. This logo actually depicts a stylus (the legs) on a record (the eye); however, the "eye" also subtly refers to CBS's main business in television, and that division's iconic Eye logo. Columbia continued to use the "notes and mike" logo on record labels and even used a promo label showing both logos until the "notes and mike" was phased out (along with the 78 in the US) in 1958. In Canada, Columbia 78s were pressed with the "Walking Eye" logo in 1958. The original Walking Eye was tall and solid; it was modified in 1960 to the familiar one still used today (pictured on this page).

Columbia changed distributors in Australia and New Zealand in 1956 when the Australian Record Company picked up distribution of U.S. Columbia product to replace the Capitol Records product which ARC lost when EMI bought Capitol. As EMI owned the Columbia trademark at that time, the U.S. Columbia material was issued in Australia and New Zealand on the CBS Coronet label.

Stereo

Columbia began recording in stereo in 1956. One of their first stereo releases was an abridged and re-structured performance of Handel's Messiah by the New York Philharmonic and the Westminster Choir conducted by Leonard Bernstein (recorded on December 31, 1956, on 1/2 inch tape, using an Ampex 300-3 machine). Bernstein combined the Nativity and Resurrection sections, and ended the performance with the death of Christ. As with RCA Victor, most of the early stereo recordings were of classical artists, including the New York Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Bruno Walter, Dmitri Mitropoulos, and Leonard Bernstein, and the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy, who also recorded an abridged Messiah for Columbia. Some sessions were made with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra, an ensemble drawn from leading New York musicians, which had first made recordings with Sir Thomas Beecham in 1949 in Columbia's famous New York City studios. George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra recorded mostly for Epic. When Epic dropped classical music, the roster and catalogue was moved to Columbia Masterworks Records.

The 1960s

In 1961, CBS ended its arrangement with Philips Records and formed its own international organization, CBS Records, in 1962 which released Columbia recordings outside the USA and Canada on the CBS label.[12] The recordings could not be released under the "Columbia Records" name because EMI operated a separate record label by that name outside North America. (This was the result of the legal maneuvers which had led to the creation of EMI in the early 1930s.)

Columbia's Mexican unit, Discos Columbia, was renamed Discos CBS.[13]

With the formation of CBS Records' international arm, it started establishing its own distribution in the early 1960s beginning in Australia. In 1960 CBS took over its distributor in Australia and New Zealand, the Australian Record Company (founded in 1936) including Coronet Records, one of the leading Australian independent recording and distribution companies of the day. The CBS Coronet label was replaced by the CBS label with the 'walking eye' logo in 1963.[14] ARC continued trading under that name until the late 1970s when it formally changed its business name to CBS Australia.

In 1962, Columbia joined in the then red hot folk music genre by releasing debut albums by The New Christy Minstrels (Presenting The New Christy Minstrels) and Bob Dylan (Bob Dylan).

In September 1964, CBS established its own British distribution by purchasing the independent Oriole Records (UK) label, pressing plant and recording studio (as well as its sold-only-in-Woolworth's Embassy cover version label).[15] The acquisition also gave Columbia and its sister labels instant access to its own roster of British recording artists to compete with during the British Invasion such as The Tremeloes.

Mitch Miller left Columbia in 1965.[16]

A small number of rock 'n' roll musicians performed for the company before 1967, notably Paul Revere and the Raiders and The Byrds.

Following the appointment of Clive Davis as president in 1967 the Columbia label became more of a rock music label, thanks mainly to Davis's fortuitous decision to attend the Monterey International Pop Festival, where he spotted and signed several leading acts including Janis Joplin. However, Columbia/CBS still had a hand in traditional pop and jazz and one of its key acquisitions during this period was Barbra Streisand. She released her first solo album on Columbia in 1963 and remains with the label to this day.

Perhaps the most commercially successful Columbia pop act of this period was Simon & Garfunkel. The group broke through in 1965 with the Tom Wilson-produced single "The Sound of Silence", which helped to usher in the so-called "folk-rock" boom of the mid-Sixties, and whose valedictory 1970 LP Bridge Over Troubled Water became one of the biggest selling albums ever released up to that time.

Over the course of the decade, Bob Dylan achieved a preeminent position, becoming arguably the most influential recording artist in the history of the Columbia label. His early 'folk' output was heavily covered by his contemporaries, and hit cover versions were recorded by many acts including The Byrds, Peter, Paul & Mary and The Turtles. Some of these covers in turn became the foundation of the so-called folk rock genre -- The Byrds' achieved their pop breakthrough with a version of Dylan's "Mr Tambourine Man", and its success in turn directly inspired producer Tom Wilson to record a new 'electric' backing track for the Simon & Garfunkel song "The Sound of Silence" (created without their knowledge or approval); when this became a surprise hit in early 1965 it revived the stalled career of the duo, who had in fact split up prior to its release.

Dylan's early albums and singles strongly influenced many of the so-called "British Invasion" acts including The Beatles, Donovan and The Animals. In the mid-1960s his controversial decision to 'go electric' and record with pop/rock-style backing groups polarised his audience but catapulted him to even greater commercial success, with his landmark 1965 single "Like A Rolling Stone" reaching #2 on the US singles chart. Following his withdrawal from touring in late 1966, Dylan recorded a large group of songs with his backing group The Band, which were originally intended as 'demos', but these recordings were heavily bootlegged over the next few years and many of these songs became hits for other artists over the ensuing years, including Manfred Mann ("The Mighty Quinn") and Brian Auger, Julie Driscoll & Trinity ("This Wheel's On Fire"); these recordings were eventually given an official release on Columbia in the 1970s under the title The Basement Tapes. Dylan's late-Sixties albums John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline also inspired a new phase of popular music, becoming cornerstone documents of the country rock genre and influencing musicians and groups such as The Byrds and The Flying Burrito Brothers.

In the wake of the Monterey International Pop Festival in June 1967, Columbia joined the rush to cash in on the new wave of psychedelic rock, signing up one of the festival's breakthrough acts, Janis Joplin, who led the way for several generations of female rock and rollers.

The 1970s

During the early 1970s, Columbia began recording in a four-channel process called quadraphonic, using the "SQ" standard which used an electronic encoding process that could be decoded by special amplifiers and then played through four speakers, with each speaker placed in the corner of a room. Remarkably, RCA Victor countered with another quadraphonic process which required a special cartridge to play the "discrete" recordings for four-channel playback. Both Columbia and RCA's quadraphonic records could be played on conventional stereo equipment. Although the Columbia process required less equipment and was quite effective, many were confused by the competing systems and sales of both Columbia's matrix recordings and RCA's discrete recordings were disappointing. A few other companies also issued some matrix recordings for a few years. Quadraphonic recording was used by both classical artists, including Leonard Bernstein and Pierre Boulez, and popular artists such as Electric Light Orchestra, Billy Joel, Pink Floyd, Barbra Streisand, Carlos Santana, and Blue Öyster Cult. Columbia even released a soundtrack album of the movie version of Funny Girl in quadraphonic. Many of these recordings were later remastered and released in Dolby surround sound on CD.

In 1976, Columbia Records of Canada was renamed CBS Records Canada Ltd.[17] The Columbia label continued to be used by CBS Canada, but the CBS label was introduced for Francophone recordings. On May 5, 1979, Columbia Masterworks began digital recording in a recording session of Stravinsky's Petrouchka by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Zubin Mehta, in New York (using 3M's 32-channel multitrack digital recorder).

The 1980s and sale to Sony

The structure of US Columbia remained the same until 1980, when it spun off the classical/Broadway unit, Columbia Masterworks Records, into a separate imprint, CBS Masterworks Records (now Sony Classical).

In 1988, the CBS Records Group, including the Columbia Records unit, was acquired by Sony, which re-christened the parent division Sony Music Entertainment in 1991. As Sony only had a temporary license on the CBS Records name, it then acquired the rights to the Columbia trademarks (Columbia Graphophone) outside the U.S., Canada, Spain (trademark owned by BMG) and Japan (Nippon Columbia) from EMI, which generally had not been used by them since the early 1970s. The CBS Records label was officially renamed Columbia Records on January 1, 1991 worldwide except Spain (where Sony acquired the rights by 2004[18]) and Japan.[19] CBS Masterworks Records was renamed Sony Classical Records. In December 2006, CBS Corporation revived the CBS Records name for a new minor label closely linked with its television properties.

Today

Columbia Records remains a premiere subsidiary label of Sony Music Entertainment. The label is headed by chairman Rob Stringer, along with co-presidents Rick Rubin and Steve Barnett. In 2009, during the reconsolidation of Sony Music, Columbia was partnered with its Epic Records sister to form the Columbia/Epic Label Group[20][21], under which it currently operates as an imprint.

Logos and branding

The acquisition of rights to the Columbia trademarks from EMI (including the "Magic Notes" logo) presented Sony Music with a dilemma of which logo to use. For much of the 1990s, Columbia released their albums without a logo, just the "COLUMBIA" word mark in the Bodoni Classic Bold typeface.[22] Columbia experimented with bringing back the "notes and mike" logo but without the CBS mark on the microphone. That logo is currently used in the "Columbia Jazz" series of jazz releases and reissues.[23] A modified "Magic Notes" is found on the logo for Sony Classical. It was eventually decided that the "Walking Eye" (previously the CBS Records logo outside North America) would be Columbia's logo, with the retained Columbia word mark design, world wide except in Japan where Columbia Music Entertainment has the rights to the Columbia trademark to this day and continues to use the "Magic Notes" logo. In Japan, CBS/Sony Records was renamed Sony Records and continues to use the "Walking Eye" logo.

List of Columbia Records artists

Affiliated labels

American Recording Company (ARC)

In February 1979 Maurice White, founding member of the R&B group Earth, Wind and Fire re-launched the American Recording Company (ARC). The Columbia Records distributed label artist roster included successful R&B, pop singer Deniece Williams and R&B trio The Emotions.

Columbia Label Group (UK)

In January 2006, Sony BMG UK split its frontline operations into 2 separate labels. RCA Label Group, mainly dealing with Pop and RnB and Columbia Label Group, mainly dealing with Rock, Dance and Alternative music. Mike Smith is the Managing Director of Columbia Label Group, Angie Somerside is General Manager, Philippe Ascoli is Head of A&R.

Aware Records

In 1997, Columbia made an affiliation with unsigned artist promotion label Aware Records to distribute Aware's artists music. Through this venture, Columbia has had success finding highly successful artists. In 2002, Columbia and Aware accepted the option to continue this relationship.

Columbia Nashville

In 2007, Columbia formed Columbia Nashville and is part of Sony Music Nashville. This gave Columbia Nashville complete autonomy and managerial separation from Columbia in New York City. Columbia had given its country music department semi-autonomy for many years and through the 1950s, had a 20000 series catalogue for country music singles while the rest of Columbia's output of singles had a 30000 then 40000 series catalog number.

Recording studios

In New York City, Columbia Records had some of the most highly respected sound recording studios, including the Columbia 30th Street Studio at 207 East 30th Street, the CBS Studio Building at 49 East 52nd Street, and their first recording studio, "Studio A" at 799 Seventh Avenue.[24]

The Columbia 30th Street Studio was considered by some in the music industry to be the best sounding room in its time and others consider it to have been the greatest recording studio in history.[24]

Columbia also had the highly respected Liederkranz Hall, on East 58th Street in New York City, a building formerly belonging to a German cultural and musical society, and used as a recording studio.[24]

See also

- List of record labels

- Sony Music Entertainment

- Sony BMG Music Entertainment

- Alex Steinweiss, the label's Art Director from 1938 to 1943, inventor of the illustrated album cover and the LP sleeve

- Jim Flora, successor to Alex Steinweiss and legendary illustrator for the label during the 1940s

Columbia Records Executives

- Rob Stringer - Chairman of Columbia Records

- Rick Rubin, Steve Barnett - Columbia Records Co-Presidents

- Mike Smith - Columbia UK Head of A&R

References

- ↑ Bilton, Lynn. The Columbia Graphophone and Grafonola -A Beginner's Guide. Intertique.com website, 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=2CMEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA35&dq=%22columbia+records%22+%2B+%22oldest+label%22&hl=en&ei=O_BXTITNHo7tnQfZma2bCQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDQQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=%22columbia%20records%22%20%2B%20%22oldest%20label%22&f=false

- ↑ Gracyk, Tim (1904-10-11). "Tim Gracyk's Phonographs, Singers, and Old Records - How Late Did Columbia Use Brown Wax?". Gracyk.com. http://www.gracyk.com/wax.shtml. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=xV6tghvO0oMC&pg=PA212&lpg=PA212&dq=%22american+record%22+%2B+columbia+%2B+%22%2470,000%22&source=bl&ots=s8cWA_uiIV&sig=blJYSuBzhwK-athm5fy0juWCMXI&hl=en&ei=-TzIS_X_D4f2MtKj1Y0J&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CAwQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=%22american%20record%22%20%2B%20columbia%20%2B%20%22%2470%2C000%22&f=false

- ↑ Solid Gospel series brings Chuck Wagon Gang to Renaissance Center.

- ↑ MILESTONES IN COLUMBIA'S HISTORY

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=liEEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA14&dq=decca+vocalion+brunswick+1941&cd=5#v=onepage&q=decca%20vocalion%20brunswick%201941&f=false

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=eQsEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA60&dq=%22CBS+Records%22+%2B+%22discos+columbia%22&cd=1#v=onepage&q=%22CBS%20Records%22%20%2B%20%22discos%20columbia%22&f=false

- ↑ Sony liner notes

- ↑ Record Collector's Resource: A History of Records

- ↑ Sony Music Entertainment Inc

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=eQsEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA40&dq=%22CBS+Records%22&cd=2#v=onepage&q=%22CBS%20Records%22&f=false

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=eQsEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA60&dq=discos+columbia&cd=4#v=onepage&q=discos%20columbia&f=false

- ↑ "Global Dog Productions". Globaldogproductions.info. http://www.globaldogproductions.info/. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- ↑ Clint Hough. "Bringing on back the good times". Sixties City. http://www.sixtiescity.com/60trivia/60trivia.shtm. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- ↑ http://www.legacyrecordings.com/Mitch-Miller/Biography.aspx

- ↑ Edward B. Moogk. "Sony Music Entertainment Inc". Thecanadianencyclopedia.com. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=U1ARTU0003271. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ By Reuters (1990-10-16). "CBS Records Changes Name". NYTimes.com. http://www.nytimes.com/1990/10/16/business/cbs-records-changes-name.html. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- ↑ Sony Music Entertainment to be Exclusive Music Provider for ESPN’s Winter X Games 13

- ↑ Columbia/Epic Label Group

- ↑ "Columbia Records Online - USA". Web.archive.org. 1999-02-08. http://web.archive.org/web/19990208003842/http://columbiarecords.com/. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- ↑ "Columbia Jazz - Main Nav". Columbiarecords.com. http://www.columbiarecords.com/Jazz/main.html. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Simons, David (2004). Studio Stories - How the Great New York Records Were Made. San Francisco: Backbeat Books. http://books.google.com/books?id=uEmmAK1qjbYC&printsec=frontcover.

Further reading

- Cogan, Jim; Clark, William, Temples of sound : inside the great recording studios, San Francisco : Chronicle Books, 2003. ISBN 0811833941. Cf. chapter on Columbia Studios, pp.181-192.

- Koenigsberg, Allen, The Patent History of the Phonograph, 1877–1912, APM Press, 1990/1991, ISBN 0937612103.

- Revolution in Sound: A Biography of the Recording Industry. Little, Brown and Company, 1974. ISBN 0-316-77333-6.

- High Fidelity Magazine, ABC, Inc. April, 1976, "Creating the LP Record."

- Rust, Brian, (compiler), The Columbia Master Book Discography, Greenwood Press, 1999.

- Marmorstein, Gary. The Label: The Story of Columbia Records. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press; 2007. ISBN 1-56025-707-5

- Ramone, Phil; Granata, Charles L., Making records: the scenes behind the music, New York : Hyperion, 2007. ISBN 9780786868599. Many references to the Columbia Studios, especially when Ramone bought Studio A, 799 Seventh Avenue from Columbia. Cf. especially pp.136-137.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||